Burning Man, 2000 - A vacation from the ordinary.

Clown Fest - Young at heart, en masse…

The July 4th Fire Island Invasion - The Grove vs. the Pines on July 4.

Renaissance Faires - The History of Renaissance Faires… Coming to a shire near you.

|

In trying to answer the question, "What is Burning Man", it is more likely that you will discover what it is not. Long time attendees will tell you that the essence of the Man is vastly different every year, that each year is a new wondrous adventure. One thing is certain, you will have a good time and you're certain to get some dust down your shorts.

Considering

the sheer size of the crowd (there were over twenty thousand souls present this

year) there were surprisingly few troubling incidents. When we arrived, a team

of friendly Greeters met us and advised us that if we didn't drink a gallon

of water by midnight our bodies would go into shock. Burning Man demanded survival;

through fierce sand storms and alternately freezing or scorching temperatures,

it is not for the faint of heart.

Considering

the sheer size of the crowd (there were over twenty thousand souls present this

year) there were surprisingly few troubling incidents. When we arrived, a team

of friendly Greeters met us and advised us that if we didn't drink a gallon

of water by midnight our bodies would go into shock. Burning Man demanded survival;

through fierce sand storms and alternately freezing or scorching temperatures,

it is not for the faint of heart.

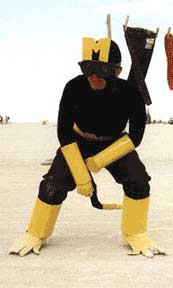

It was quite the heady experience, however, to be suddenly surrounded by thousands of highly artistic individuals in a myriad of outrageous costumes. The sheer talent present overwhelmed us. Many people had already been at the site for two or three months, setting up their unique art installations in anticipation of Burning Man. In the future, Burning Man may be known as the premier step in outing an artist and gaining exposure.

One axiom that does not hold true at Burning Man is "it's money that matters".

In fact, there is rarely much to purchase beyond a hot chai or some ice bags.

Money can't buy the art because the art, every spectacular piece of it, is set

to burn, baby burn. For the observer, this was a grand opportunity to interact

with the artist on a personal level. The artist usually  hovers

around their work, and can be seen intermittently darting in and out of various

theme camps. The art is up close and dynamic, and the artists remain accessible.

It was an art aficionado's dream come true, and the least interested attendee

will still have much to gain just by keeping their eyes open.

hovers

around their work, and can be seen intermittently darting in and out of various

theme camps. The art is up close and dynamic, and the artists remain accessible.

It was an art aficionado's dream come true, and the least interested attendee

will still have much to gain just by keeping their eyes open.

As for the artist, they have stumbled upon their own transitory slice of heaven. Freedom from dealers, galleries, critics, and even, for the most part, the media as they are tightly controlled at Burning Man. For example, this past year, Playboy was denied media access. There existed a certain level of privacy in the desert - it was a democratic sphere where the middle-man was swiftly eliminated. The art and the observer converse freely wearing nothing but body paint, and no one would think it strange. In fact, you'd be hard pressed to stick out at Burning Man, unless you were wearing a three piece suit. The majority of the dust-battered folks here were in costumes and wigs, or completely nude. It was an artists' sanctuary, a place of refuge from an otherwise demanding world.

The

ideal at Burning Man is to create a friendly, accepting environment for self-expression.

A comfortable oasis that offers a non-judgmental arena to just be. The motto

seems to be: Be yourself, or even freer than you could have imagined yourself

to be, and somehow it worked on a grand scale. The creators of Burning Man want

you to be yourself, in peace, but they also want you to be a part of it all.

As much as expansion of the self in terms of individuality was encouraged, active

participation was central here. Impromptu bongo music, dance, and poetry readings

were the norm at center camp. There were over a dozen theme camps and villages

in full swing, many of which centered upon personal interaction. The free flow

of energy was necessary for the success of the ideas present.

The

ideal at Burning Man is to create a friendly, accepting environment for self-expression.

A comfortable oasis that offers a non-judgmental arena to just be. The motto

seems to be: Be yourself, or even freer than you could have imagined yourself

to be, and somehow it worked on a grand scale. The creators of Burning Man want

you to be yourself, in peace, but they also want you to be a part of it all.

As much as expansion of the self in terms of individuality was encouraged, active

participation was central here. Impromptu bongo music, dance, and poetry readings

were the norm at center camp. There were over a dozen theme camps and villages

in full swing, many of which centered upon personal interaction. The free flow

of energy was necessary for the success of the ideas present.

There was the human petting zoo where one could cuddle up next to people donning

various fur costumes. At Burning Man, you could slither down a slide in the

form of a vagina, or swing on a trapeze twelve feet above the ground. Or if

you were brave enough, take on an opponent in the gothic underworld of the Thunderdome.

Here you'd be launched through the air, lunging at each other on flying harnesses.

Walking across the desert, you were destined to meet people and participate,

be it in the walk through the maze (a la Minotaur), or at Costco, the Soulmate

Trading Outlet. In this tent, your fate was  surreptitiously

sealed with another after a short comical application process. Of course, sexual

orientation was honored, and there was much exploration in the field of sexuality

at the Man, especially since this year, "The Body" was Burning Man's theme.

surreptitiously

sealed with another after a short comical application process. Of course, sexual

orientation was honored, and there was much exploration in the field of sexuality

at the Man, especially since this year, "The Body" was Burning Man's theme.

And, if you were feeling a little frisky, you could stop in the Peep Show Shack,

which was designed so that exhibitionists and voyeurs could find each other

without interruption. For those that had pent up aggression, or just wanted

to bang on metal to test their musical inclinations, an art installation catered

to this exact whim, in the tradition of Stomp, the musical. Except at Burning

Man, ideally, there was no audience. You just walked up, grabbed a couple of

drumsticks off the dry ground, and started jamming. If you were a little on

the shy side, you could catch any one of the performances available, such as

the ongoing opera or the Psychotropic Stardust Theater. At the latter, the play

"Messiah 2000" informed all in their quest for the Messiah, that if there is

a God, he'd definitely show up at Burning Man. Also at the sparkling pink Stardust,

Gabby serenaded the crowds on her sitar, much to everyone's delight. Perhaps

the most astonishing performance was by the man who  courageously

conducted electricity on a platform twenty or so feet in the air, using his

helmeted head as a mid-way point between two domes, and then even using his

derriere. I still haven't figured that one out. For those that missed their

childhood years, a giant see-saw provided a wonderful view of the goings-ons.

courageously

conducted electricity on a platform twenty or so feet in the air, using his

helmeted head as a mid-way point between two domes, and then even using his

derriere. I still haven't figured that one out. For those that missed their

childhood years, a giant see-saw provided a wonderful view of the goings-ons.

The thing that makes Burning Man so dynamic may be its undefinable nature.

It is not a festival with the same attractions every year. Next year is guaranteed

to be its own unique landscape, so returnees can always explore new ground.

The atmosphere was extremely friendly. I had constant offers ranging from food

and drinks, to showers. Those that came well prepared or had RV's helped those

stumbling through the dust storms. Many had thought to bring surgical masks

to protect their throats from the scratchy dust. Stumbling through the storm

myself on the way back to my tent, I was kindly asked several times: Hey, do

you need a place to go?

Some may say they enjoyed dancing at the raves the best - cutting a rug at Bianca's or the Jiffy Lounge. Others will cite the art installations, or the Burning of the Man itself. Some describe the socio-political environment as ideal in particular the spirit of radical anti-commercialism present. In fact, this attitude was so prevalent that I was told quite seriously, "you could get arrested for wearing that watch at Burning Man." No matter where your interests lie, it seems the desert offers something for everybody. It is an extremely unselfconscious city, where you can be, at least for one week, comfortable just existing. Not having to do anything in particular. Needless to say, this attitude is refreshing in a world of ever increasing demands and emerging technologies.

On a more personal note, I was advised that to get the full experience, just take the year's transgressions and burn them along with the man. To bring any troubling issues and just let them go. Many bring pictures, letters, and sentiments to toss into the flames of the after-burn. After a year marked by the loss of a trusted grandmother and a dear friend, how cathartic to just let it all hang out, to hurl my tribulations into the smoky night. For me, Burning Man was highly therapeutic. It was a huge leap in healing through the loving souls I met, through both distance and connection. I can't wait for next year.

To many, September is a time to of transition from the carefree days of summer to the more serious seasons of fall and winter. To a few proud souls, however, September is a time of spring colors, toys and some serious silliness.

The second week of September is the date of the annual pilgrimage of hundreds of clowns to the scenic beach town of Seaside Heights, New Jersey.

And what do these clowns do, you ask?

Negotiate world peace?

Discuss free trade?

Fight for truth, justice and the American way?

Well… yes… And they seem to be doing a much better job than the clowns in Washington DC. (de-dump-dump).

As these good-will ambassadors promenade down the boardwalk, they share warmth, smiles, stale jokes and wacky antics with anyone who cares to give them a second look. These five days of fun include many family friendly events including the Clownfest Big Top Circus, the outrageous "Run for the Noses" competition, various family oriented workshops and the Grand Finale - The Clownfest Boardwalk Parade. This Parade is the largest event of its kind and features thousands of the happiest people you'll ever meet.

With names like Zooky, Trumpet, P-Nut and Scooter, these clowns range from age five to eighty and have love in their hearts and a variety of whistles, hooters and honkers in their pockets. And yes, young children either stare with rapt attention or curl up in terror as these monstrous, multi-colored monsters approach them waving various baubles and props.

Childhood terror, notwithstanding, these particular clowns are the most well-meaning breed. This was not an Evil Clownfest (although if there is such an event, Costume Network needs to know!) nor was this a Clown Rodeo with clowns wrangling various large angry mammals. These clowns are just good people who do not take themselves too seriously and like to make people happy.

July 4th… A time for family, barbecues, beaches, baseball and… cross dressing ??? Well, it is America and July 4th is Independence Day, sweetheart…

And this is the Pines Community in New York's Fire Island. Just off the coast of Long Island (1-2 hours from New York City with a 30 minute ferry ride), Fire Island is a 30-mile long series of beach communities with no automobile traffic and a diverse group of small neighborhoods. Connected by boardwalks and slim roads that barely allow for the passage of the occasional Police jeep, Fire Island is a beautiful place that immediately gives visitors the feeling that they are in another world.

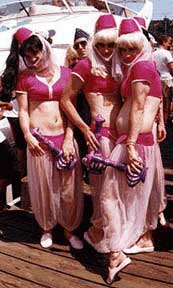

And the July 4th Invasion is certainly no exception. This annual tradition began in the early 70's allegedly when members of the Cherry Grove community, tired of playing second fiddle to the more prestigious Pines Community, decided to "invade" their neighbors in their finest evening wear.

Since then, this event has become an annual party when hundreds of the Island's most beautiful souls board a ferry in Cherry Grove to storm the beaches (actually the boardwalk) in the Pines' harbor. Thousands of people from all over Fire- and Long- Island jam the docks to hoot and applaud the efforts of this enthusiastic bunch. With a Master of Ceremonies at hand, each invader struts off the ferry and down the runway-like pier in an effort to outdo their friends and neighbors. A day of costuming and camaraderie for a great group of folks.

If you would like to share some stories or post photos from the Invasion or any other costuming event, please contact us.

.jpg)

The world of Renaissance Faires now covers the entire nation, and has sent

its roots out across the globe. An estimated 10 million Americans visited faires

last year, and each spring season enthusiasts see the birth of new faire sites

on the country's back roads and interstate highways. Renaissance weddings have

entered the mainstream, and the number of armorers and costumers making a solid

living by the design of gauntlets and lace has reached an astonishing level.

From children to retirees, the whole world seems to be reveling in the spirit

of Things Medieval and Renaissance. But over thirty years ago, no one had ever

heard of Renaissance Faires. What is the story of this ever-changing and multi-colored

creation?

How did this motley phoenix rise from the dust?

.jpg) The

Genesis of the Faire

The

Genesis of the Faire

The early 60s were still a time when people believed in the post-war mantra of the assembly line. Anything handmade, or knitted by a grandmother, was considered a laughable relic of pre-modern times. The explosion of colors and fabrics in the world of style had not yet occurred, and if anyone still cared about the intricacies of arts and crafts, they kept their knowledge to the privacy of their own homes. In short, the crafts movement was only a whisper in the dark.

At about this time, a young mother in Southern California had recently quit her teaching job to raise children. Phyllis Patterson had come from a family of educators, and her desire to communicate her ideas and enthusiasm for history and drama was spilling out over the confines of traditional motherhood. She had grown up on a small family farm in Nebraska in a friendly atmosphere of direct involvement among neighbors. As a bored mother in Laurel Canyon, CA, a suburban community near Los Angeles populated at the time with Hollywood people, she responded to an ad in the local Canyon Crier to be Director of a "summer workshop" for children.

At the Wonderland Youth Center, she organized the summertime activities of

80 children from local families, all from six to 12 years old. At first, Patterson

admits, she had no idea what to do. Her father had taught her the educational

wisdom that the classroom "should be like a circus." The Hollywood parents of

her campers were proposing a theater workshop. So, to produce a camp activity

that would be fun and educational, Patterson came up with the idea of putting

on a History of Drama. The youngest children would perform as cavemen, while

later groups would put on a Greek Chorus, Chinese Theater, followed by a Medieval

Stage, and Shakespeare presentation. Using this straight-line "Victorian" approach

to the past, the children staged impromptu 10-minute versions of World History..jpg)

Most of the segments were fairly easy to write and produce. Problems only arose

for Patterson with the medieval section. To her mind at the time, medieval drama

was dull, and moralistic, and hardly an exciting dish to serve up to children.

By chance, a friend recommended the book by Duchartes called The Italian Comedy,

which tells the story of medieval improvisational players who traveled about

the countryside in their carts, performing the comedies of Harlequin and Columbine.

These wandering players were daring masters of what Patterson calls a "guerrilla

theater," quite politically and socially subversive, which spoofed all of the

customs of the social order. They would come seasonally to the city square,

and set up their carts to perform. The version of the Comedia plays that Patterson

scripted, and even built a makeshift cart to perform upon, was an instant hit

with her summer children.

In the off-season, they continued to "hassle" her about the Comedia skit. To expand on the cart-show, she looked into the woodcut drawings in the Comedy book to try to imagine what the surroundings of the lowly cart in the town square might have been. It occurred to her that the players would arrive in town in springtime when the roads were dry, and the local market was established. Around the players, merchants hawked their wares, and townspeople high and low engaged in a busy market scene. It pleased Patterson's imagination to envision an interactive environment, where everyone from the theater players to the vendors and visitors were engaged in a lively exchange of words and wares. To her, this was a far cry from the stodgy repetition of traditional theater, and closer to the lively repartee of what was at the time a blossoming mode of performance - improv theater.

Patterson was a fan of the BBC radio plays and sound collages of the time, and she knew people who worked in the local KPFK radio station, a version of the early Listener Supported Radio, the precursor of Public Radio. Since the fund-raising practices of the early days of public radio were in need of help, Patterson had a brainstorm idea. On January 25, 1963, her birthday, it occurred to her that she could produce a Medieval Faire, based on her ideas of the market fair surrounding the Comedia cart, which could be used as a fund-raiser for the radio station. As she says, "It was designed to be the exact antithesis to the PTA carnival, where people gathered on black-top for pie and teacher-dunks." In her mind, people had celebrated for 1000 years on grass and dirt, amid trees and fields. Her fair would be like a town market fair in a natural setting with no amplifying systems, and no asphalt. The Nebraska farm girl and teacher's daughter in her had evidently spoken up.

She presented the idea to the board of directors of the radio station, which

consisted entirely of grumpy ACLU lawyers disgruntled by the station's seemingly

permanent lack of funds. At first, the directors were not at all excited about

the idea. According to Patterson, one said, "I don't want anything to do with

the Middle Ages - there were no civil rights then." (Patterson says that if

she had known more about the period, she could have informed the gentleman that

in fact many of our modern liberties derive from the Middle Ages.) As a result,

Patterson mused to herself that since faires did not change that much in the

next period, why not simply have a Renaissance Faire? It was a brighter period,

with all the glamour of Elizabeth and Shakespeare. It could still contain the

best aspects of the Medieval Faire, and would be just as fun. In this change,

the idea of the

Renaissance Faire was born.

The First Renaissance Faire

The Faire was scheduled to take place on Memorial Day weekend in May, and Patterson

was given a half-hour radio spot once a week to promote the event. In an enormous

room, she plotted out the different duties and committees on butcher paper,

and volunteers signed up for various jobs. Many of the parents of children from

her summer theater pitched in, and eventually over 500 volunteers were recruited.

A five-acre country location was found for the event, with a small house that

Patterson covered with a facade. "We wanted to have as few distractions as possible

which would take people out of an immersion in the time period," she adds. The

Comedia cart was set up,

surrounded by makeshift small booths built by the volunteers.

At first it was very difficult to find craftspeople that had any knowledge or expertise in traditional arts and crafts. The burgeoning of the handcrafts culture had not yet occurred, and there was no buying audience for handmade things: "I said to myself - I wonder if anyone makes anything by hand anymore? At first all I could find was one sandal maker!" Eventually she turned up a number of potters who made their wares for themselves, some weavers, and a handful of other hobbyists. 65 craftspeople manned the rickety booths of the first faire. At first, faire visitors were unimpressed, and would make comments like, "Oh look, a pot! Well it looks nice, but it costs too much for a pot". "After considering the situation," she says, "I knew we were going to have to re-educate an entire audience."

The early costumes of the faire were simple, and quickly patched together. At first it was difficult to get the men to wear tights, so many settled for the flops of the Renaissance period. Basic costumes were rustic dresses with ribbons, or the lace dresses which girls and ladies made from their mothers' tablecloths. There were no boutiques for costume wear, so everything was done at home. "It is always difficult," says Patterson, "to know if you are ahead of the wave, or if you are the wave. But I know that the colors of the 60s came from the faires."

So in May of 1963 for a weekend of 2 days, 500 volunteers and 3,000 visitors

caroused for no charge at the charming country location, and were the first

to taste the simple excitement of faire life. Many of the dramatic performers

at the faire were drawn from those with community theater experience. The philosophy

of performance that Patterson envisioned was a mix of improv and Comedia styles.

Her goal was always to break down the "fourth wall" between the stage and the

audience, so that the experience of immersion could combine with participation.

She wanted the people who came to the faire to play as large a part in the spectacle

as they wanted: "The idea behind the Renaissance Pleasure Faire was to include

as much choice as possible on the part of the visitors. If they choose, they

are as much performers as the actual performers."

The Expansion of the Faire

The first site of the faire was quaint, but imperfect. As Patterson and her organizers looked around for a new site, they were taken to the location of the Paramount Ranch. This spot had been once used to shoot Robin Hood movies, and was dotted with beautiful 500-year-old oak trees. Seated in a gorgeous hidden valley, with a forest just behind it, it was to Patterson an overwhelming sight. Here she had found the perfect setting for her faire, with none of the obstacles to a complete immersion in an older time.

At the new location, the faire was held in 1965 for three days, with an attendance of 7,000 per day. By 1966, the faire had expanded to two weekends, with nearly 12,000 visitors per day. The first layout included several half-round, thatched stages, 3/4 size craft stalls, pageants and parades. None of the stalls or stages were permanent structures, but rather were designed to lend a "seasonal" and impermanent quality to the gathering, as it would have been in olden times. Exhibits featured a Queen's Parade, an assortment of Morris Dancing, quiet music, plays and skits, mock hangings, a shame cart, fool's parade, and a country glade. One performance showed a group of rustics presenting themselves to a Lord Mayor. Plays drew their substance from a range of material from Chaucer to Shakespeare.

With the success of the faire, it gradually grew from one weekend to six by

the mid 70s. Originally a spring event planned to coincide with the time of

the May festivals, it soon was also held in the fall at the harvest time. One

of the major changes that Patterson points to over this period of development

was the introduction of a guild system. She says it developed simply to help

cope with the size and number of visitors and volunteers. Soon specific groups,

like the Scots or Irish, the peasants, the fools, and many others were formed

into guilds. Guilds were given their own gathering areas, where people could

visit them working and eating, and interact with them in their "natural" settings.

Another innovation was the use of Faire-Ever Tags, which allowed visitors to

enlist themselves into social classes. Green was for peasants, rust for merchants,

purple for nobility, and gold for fools - according to Patterson, the most noble

of all. Curiously, she says, few people chose the middle-class "merchant" color,

but most preferred to go "up"

or "down" in the social hierarchy.

At first, of course, performers and vendors all offered their help on a volunteer

basis. But as time went on, money was distributed to the guilds, and to performers

like dance-groups, stage actors, and musical ensembles, though the amounts were

still relatively modest at about $100-200. As the flavor of faire life, and

the interest in the arts and crafts penetrated the consciousness of California

and the nation, craftspeople were able to begin making a living selling at the

faire. Eventually, many of them took in their yearly earnings over the two faire

weekends. Clearly, after its first awkward, but playful steps, the spirit of

faire life, along with the participation and enthusiasm of all varieties of

people, had joined hands with the spirit of the times. The vision of Phyllis

Patterson on her birthday in 1963 had produced a new playland for the dramatic

and historical imagination called the Renaissance Faire.

The Descendants of the First Renaissance Faire

With the success of the faire idea, it would not be long before the people involved in the first faire would try to create their own faires across the country. George Coulam manned a glass booth at the Patterson faire, but soon decided to branch out and create a faire of his own. He established the Minnesota Faire in the early 70s, using an amalgam of ideas that did not necessarily limit themselves to the small setting of the Pattersons' vision.

In fact, he looked elsewhere for his inspiration, and found it in the proven entertainment model of Disney. "It was Phyllis Patterson who invented the theme, but Disney invented the structure and model," says Coulam of his own philosophy of faire design. "I read Disney's book over about five times, and then took what I learned from it to make the Minnesota Festival." He found a location that he rented from the owner for $1 a year, and set up a permanent village of houses, stages, and booths.

To recruit performers and vendors, he ran ads in local crafts magazines. As an artist himself, Coulam adds that he was especially sympathetic to his artists and performers, and treated them with great respect. According to the Disney model, the faire was established to entertain its visitors in increments, first exposing them to some arts and crafts booths, then a major stage area, then street characters and skits, then another major stage, and so on. The idea was designed to have faire goers work themselves progressively around the faire area, and take in the entertainment in pieces, much like at Disney World.

In terms of styles, Coulam says that the Minnesota Festival drew its inspiration from a mixture of the English and Italian Renaissance. He considers the Italian to represent all of the high tastes of the modern idea of the Renaissance, with a focus on painting, sculpture, and the high arts. The English model contains the bawdy elements, with low humor, high spirits, and small town life. Together these made a perfect combination, providing both "merry humor" and "refinement". Coulam attributes the genesis of the market faire historically to a co-operation between the "gypsies and dukes" who staged the first horse races, which later became similar to what we know as state fairs.

In the early days, Coulam had the goal of attracting 25,000 visitors a day for fourteen days. His goal was soon reached, and his model was so successful, that he sold the Minnesota Festival, and went south to found the Texas Renaissance Festival, to this day one of the biggest and most successful faires. According to Kevin Patterson, son of Phyllis Patterson, and head of As You Like It Productions, most of the major faires in America were direct copies of Coulam's Minnesota model. This model involves the idea of erecting permanent town-like structures that essentially strive to re-create an English Town or Village. Though Patterson laments the spread of this model because he believes it takes away from the spontaneous "seasonal market" appearing at the edge of town, it has proven the version most able to accommodate the largest number of visitors.

The success of this model, admits Coulam, probably has do to with the fact

that "very few people in the general public know anything about the Renaissance.

The hard-core people who do know a lot are the one who are performing on stage

or selling in booths." His goal, he adds, was always to provide a setting in

which people could have fun. "I basically wanted folks to laugh, and enjoy themselves,

and have a good time. I hoped the experience would be even better than Disney."

The Modern Renaissance Faire

If many of the Faires that followed the lead of Coulam's Minnesota and Texas ventures shared the characteristics of the English Town model, the same cannot be said of more recent developments in faire life. Bobby Rodriguez, who runs the Florida Renaissance Festivals North and South, says that when he first looked into starting a medieval theme festival in the early 90s, he recognized that most renaissance faires were based upon "the idea of an English Renaissance village, whether Tudor or Elizabethan." He saw an opportunity to create a new kind of faire, one that would more accurately represent the diversity and variety of cultures that truly made up the Renaissance. "As a European phenomenon," he says, "I felt that all countries and cultural influences of the Renaissance should be represented, whether Spanish, Italian, German, French or other."

As a result, he preached to his staff that he wanted his faire "to get outside the box" of what had become the industry standard for faires. In the past years, this new approach has produced some exciting results, as Rodriguez has made efforts to pull in talent from all over the world. He recently had musicians and dancers from the Ivory Coast, for instance. One of his hopes for the future is to have a large representation of performers depicting Renaissance Japan, the Shogun period. "At the same historical moment, they too had their archers, their master armorers, and their warriors and entertainers," says Rodriguez.

Rodriguez' approach may indeed indicate a trend for the future of renaissance faires. He says that he has spoken with a representative of the International Events Corporation, a premier sponsorship organization of events around the world, which indicated that the future of big festivals would be based upon this international model. Another possible trend may be in George Coulam's plans for the Texas Renaissance Festival. He has already developed his next phase, which will include four large new garden-areas.

These slanted gardens will be filled with flowers and trees, and "romance," according to Coulam. Separate altars will be dedicated, for example, to "Love" or "Money" or "Cures," and visitors can stroll about the gardens at their leisure. Perhaps the "Magic Garden" idea in some way hearkens back to the lost tranquility of the original pastoral setting of the first Patterson faire. In this sense, the long history of expansion and growth of renaissance faires may indeed have come full-circle and regained a taste of its origins.

Of course, these are simply some of the larger patterns of development which have marked the development of that charming institution we call renaissance faires. There are now faires of nearly infinite variety, and each one has its own unique flavor and feeling. The only real way to experience the history of renaissance faires is to have lived through them, or to attend as many as possible in the future.

But one characteristic marks the special feeling which faires have been able to pass on to their visitors over the years, and it finds its roots in Phyllis Patterson's original sense of creating an interactive experience, involving a high level of choice and participation not just for performers, but for visitors. In her dream, visitors would be performers too. This dream has certainly not been lost in all of the years and versions of faire life.

It is close to what Bobby Rodriguez points to as the central element in a successful faire: "People love actually to touch and see different cultures, peoples, and performers. But the key to the success of any faire lies not only in the presentation of an era, but actually in the interaction with the audience.